Die Arbeiten „Gewebe“ wurden in der Leica-Galerie Wien gezeigt:

Changing Perspectives, Jon Ball, Fred Mortagne, Sabine Wild

Leica Galerie Wien, Seilergasse 14, 1010 Wien, 16.06. bis 09.09.2023

Interview im Leica-Blog, August 2023

LFI-Blog Sabine Wild: Stürzende Linien, August 2023

Interview im Leica-Blog LFI, August 2022

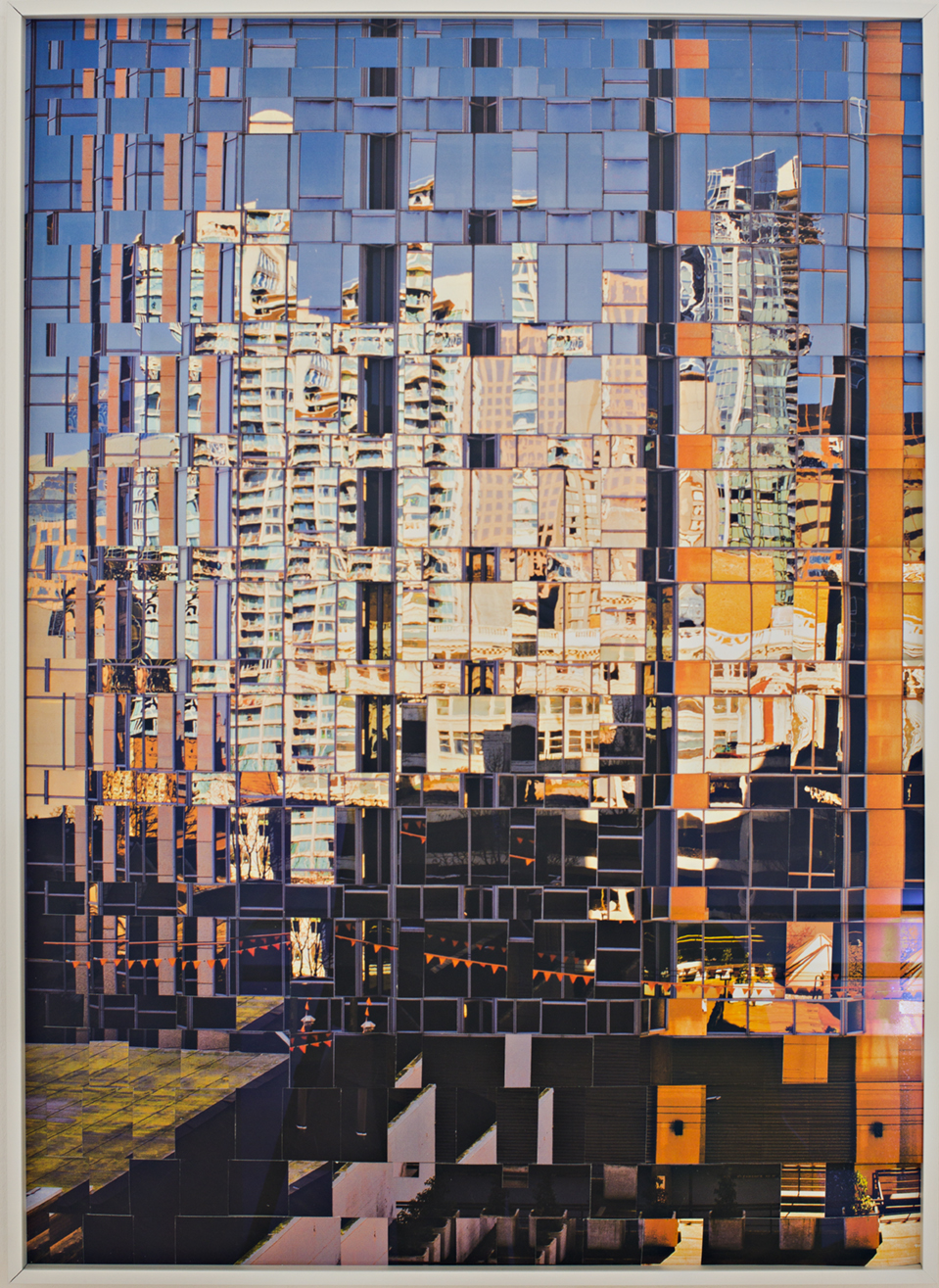

Kunstmuseum_Stuttgart_L007244, 2009/2023, 59,4 x 84 cm, Pigmentprint auf Hahnemühle Photorag, Aluminium-Distanzrahmen, Museumsglas, Unikat

Mercedes_Museum_L007232, 2009/2023, 59,4 x 84 cm, Pigmentprint auf Hahnemühle Photorag, Aluminium-Distanzrahmen, Museumsglas, Unikat

Porsche_ Museum_Stuttgart_L1007237, 2009/2023, 59,4 x 84 cm, Pigmentprint auf Hahnemühle Photorag, Aluminium-Distanzrahmen, Museumsglas, Unikat

Porsche_ Museum_Stuttgart_L1007241, 2009/2023, 59,4 x 84 cm, Pigmentprint auf Hahnemühle Photorag, Aluminium-Distanzrahmen, Museumsglas, Unikat

Staatsgalerie_Stuttgart_L1007238, 2009/2023, 59,4 x 84 cm, Pigmentprint auf Hahnemühle Photorag, Aluminium-Distanzrahmen, Museumsglas, Unikat

Neue_Nationalgalerie_L1004852, 2023, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen,

Museumsglas, 59,4 x 84 cm, Fotografie, von Hand gewebt, Unikat

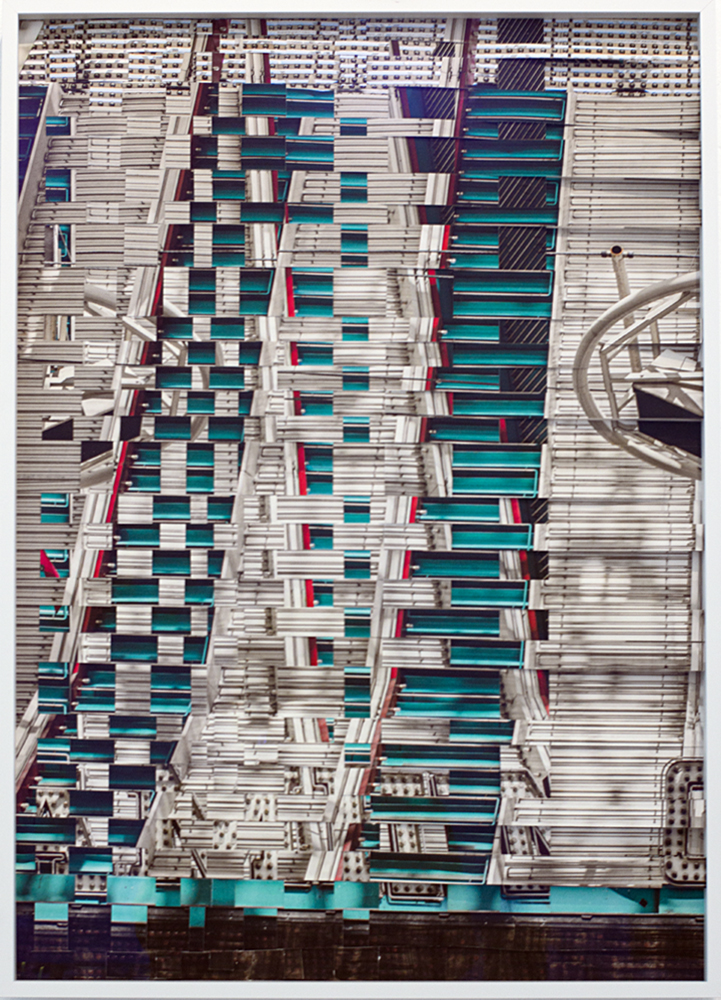

Am Lokdepot 45 Berlin, 2023, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen,

Museumsglas, 60 x 120 cm, Fotografie, von Hand gewebt, Unikat

Brooklyn_Bridge_L1003249, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen,

Museumsglas, 60 x 120 cm, Fotografie, von Hand gewebt, Unikat

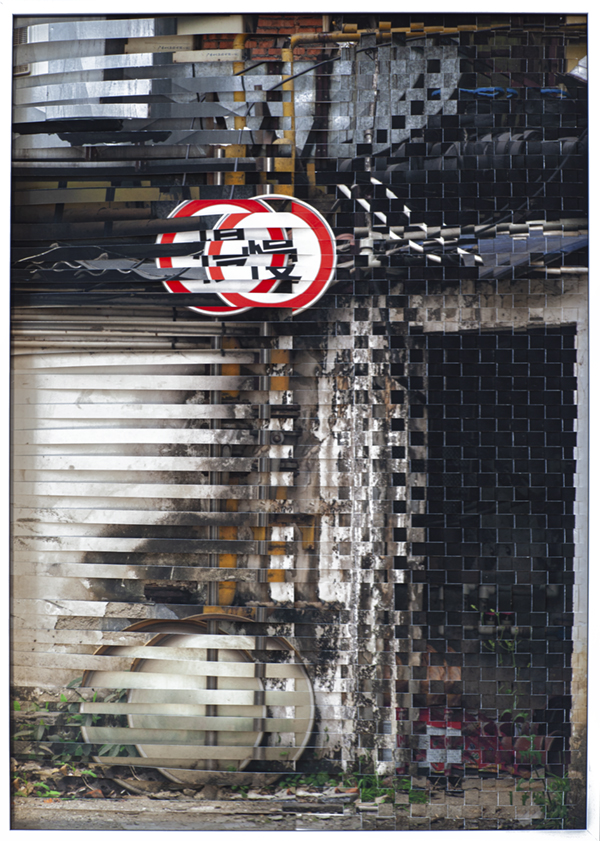

Cuba_Havanna_L1004841, 2023, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Aluminium-Distanzrahmen,

Museumsglas, 59,4 x 42 cm, Fotografie, von Hand gewebt, Unikat

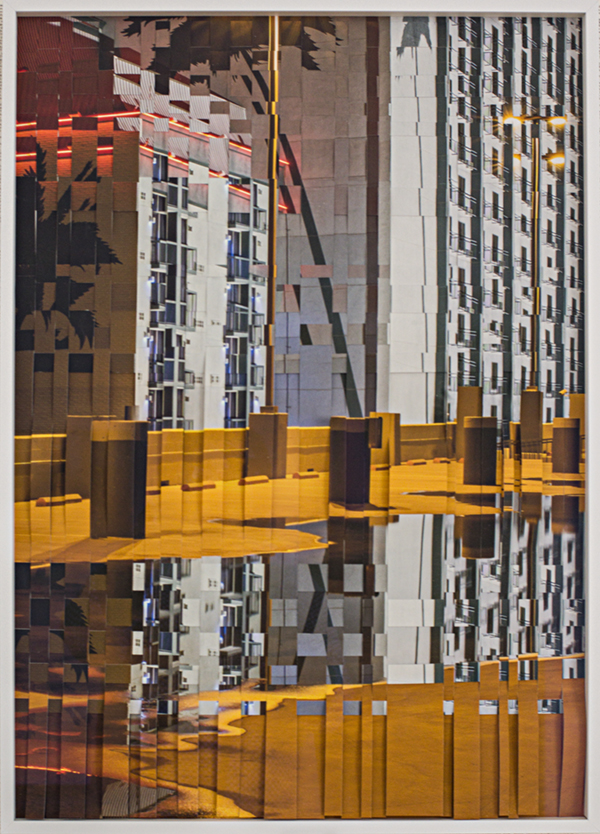

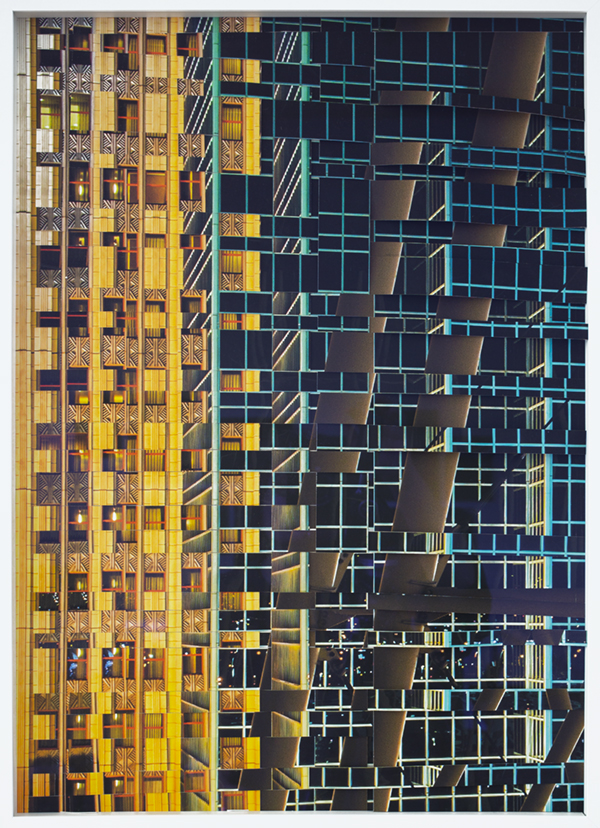

Las_Vegas_L1002464, 2023, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen,

Aluminium, Museumsglas, 59,4 x 42 cm, von Hand gewebt, Unikat

Las_Vegas_L1002466, 2023, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen,

Aluminium, Museumsglas, 59,4 x 42 cm, Unikat, von Hand gewebt

Las_Vegas_L1002469, 2023, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen,

Aluminium, Museumsglas, 42 x 59,4 cm, Unikat, von Hand gewebt

Las_Vegas_L1000589, 2022, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen,

Aluminium, Museumsglas, 84 x 59,4 cm, Unikat, von Hand gewebt

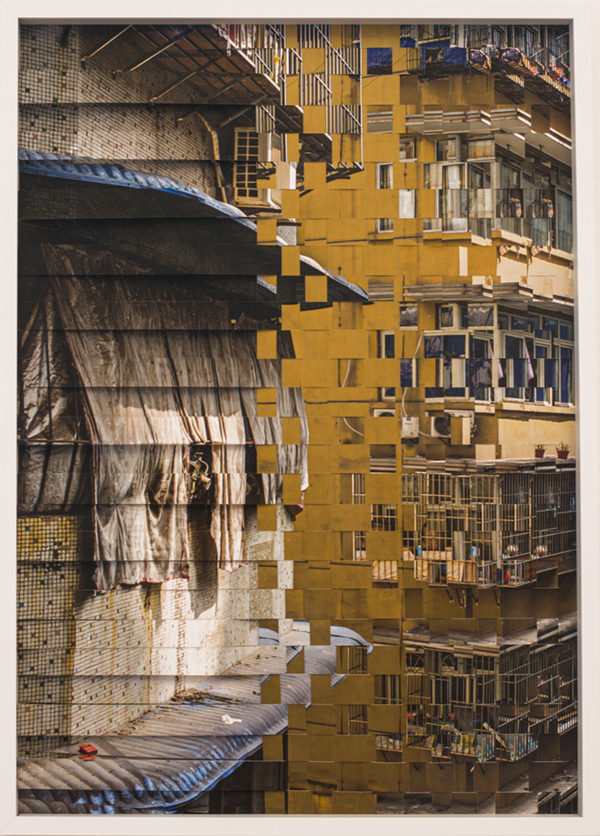

Chonqging_L1000585, 2022, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen,

Aluminium, Museumsglas, 42 x 29,7 cm, Unikat, von Hand gewebt | sold!

„New York_L1000582“, 2022, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen,

Aluminium, Museumsglas, 84 x 59,4 cm, Unikat, von Hand gewebt

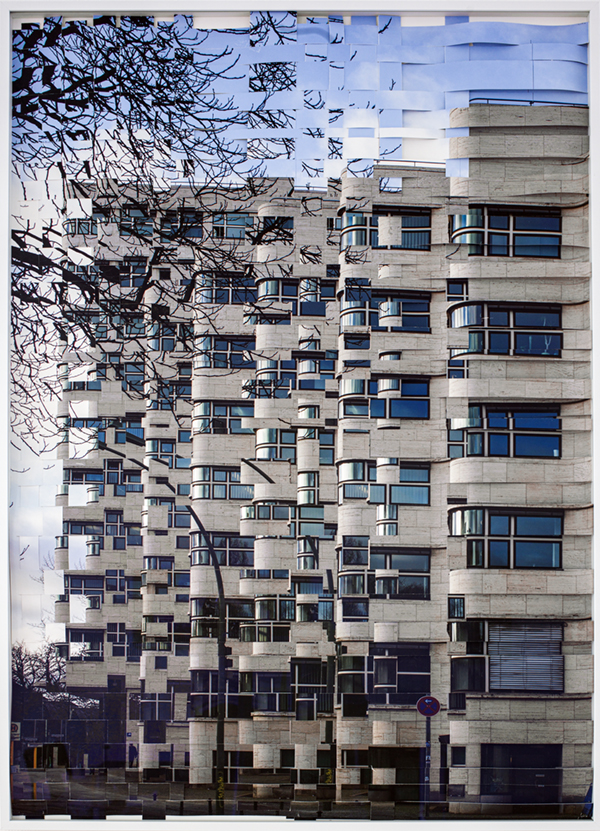

„Shell-Haus_L1000575“, 2022, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen,

Aluminium, Museumsglas, 84 x 59,4 cm, Unikat, von Hand gewebt

Las Vegas L1000580, 2022, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen,

Aluminium, Museumsglas, 59,4 x 42 cm, Unikat, von Hand gewebt / sold!

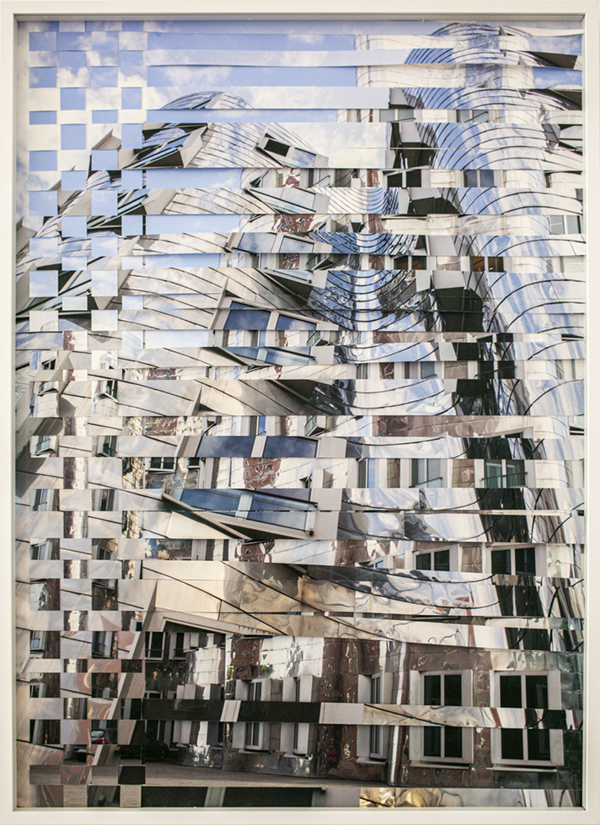

„L1002494“, Haus B von Frank O. Gehry, Medienhafen, Düsseldorf, 2022

Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen, Aluminium, Museumsglas,

59,4 x 42 cm, Unikat, von Hand gewebt / sold!

„L1002498“, Haus A von Frank O. Gehry, Medienhafen, Düsseldorf, 2022

Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen, Aluminium, Museumsglas,

59,4 x 42 cm, Unikat, von Hand gewebt / sold!

Seattle L1002531, Museum of Pop Culture, Frank O. Gehry, 2022

Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier, Distanzrahmen, Aluminium, Museumsglas,

59,4 x 42 cm, Unikat, von Hand gewebt / sold

Las Vegas L1001550, 2022, 59,4 x 42 cm, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier,

gerahmt, Museumsglas, Unikat, von Hand gewebt / sold!

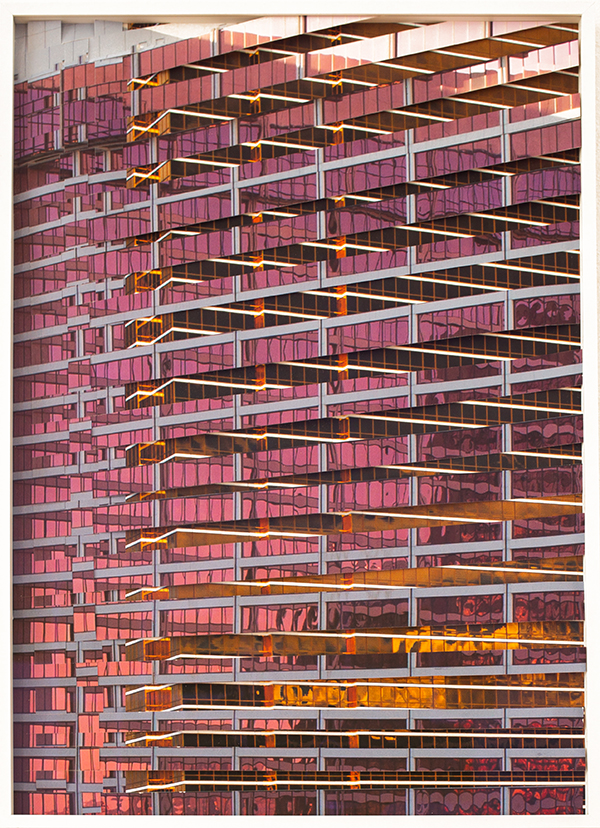

Las Vegas L1001533, 2022, 59,4 x 42 cm, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier,

gerahmt, Museumsglas, Unikat, von Hand gewebt

Las Vegas L1001552, 2022, 59,4 x 42 cm, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier,

gerahmt, Museumsglas, Unikat, von Hand gewebt

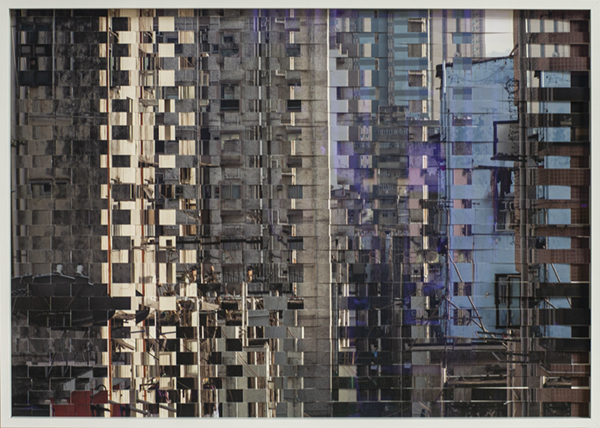

HongKong L1001469, 2022, 42 x 59,4 cm, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier,

gerahmt, Museumsglas, Unikat, von Hand gewebt | sold!

Las Vegas L1001532, 2022, 84 x 59,4 cm, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier,

gerahmt, Museumsglas, Unikat, von Hand gewebt

Las_Vegas_L1000343, 2021, 59,4 x 42 cm, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier,

gerahmt, Museumsglas, Unikat, von Hand gewebt | sold!

Chengdu_2978, 2021, 59,4 x 42 cm, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier,

gerahmt, Museumsglas, Unikat, von Hand gewebt

Chonqging_L1009590, 2022, 42 x 59,4 cm, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier,

gerahmt, Museumsglas, Unikat, von Hand gewebt / sold!

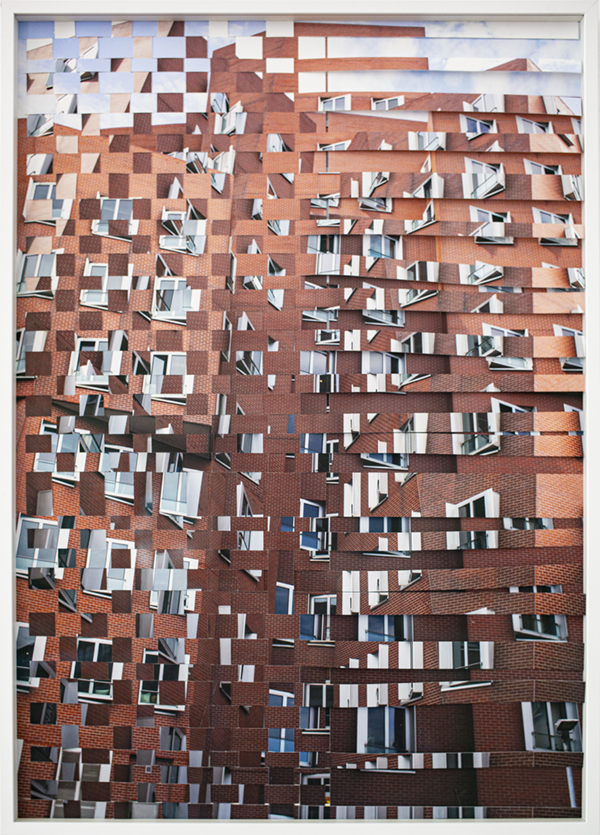

Hongkong_9328, 2021, 84 x 59,4 cm, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier,

gerahmt, Museumsglas, Unikat, von Hand gewebt

Chongqging_3754, 2021, 59,4 x 42 cm, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier,

gerahmt, Museumsglas, Unikat, von Hand gewebt | sold!

Chongqing_L1003792, 2021, 59,4 x 84 cm, Pigmentprint auf Baumwollpapier,

gerahmt, Museumsglas, Unikat, von Hand gewebt

Gewebtes Stakkato (please scroll down for the English version)

Mit Begeisterung eigens erstellte Fotografien zu zerschneiden, ist ein aggressiver Akt. Mit dem Cutter fahre ich entlang der stürzenden Linien eines in die Jahre gekommenen Hochhauses in Hongkong, Kowloon, und schneide das Foto im A1-Format in vertikale Linien (bis auf den obersten Zentimeter, damit die Streifen nicht auseinander fallen). Nun nehme ich mir den zweiten Druck des identischen Motivs noch einmal vor und folge mit dem Messer den horizontalen Linien entlang der Fenster- und Balkonbrüstungen. Als würde ich die Architektur des Hauses mit seinen Vorsprüngen, Klimaanlagen, Fenstergittern liebevoll nachzeichnen. Ich halte lose schmale Streifen in der Hand, die ich rückseitig nummeriere.

Jetzt greife ich eine alte Kulturtechnik auf und webe die horizontalen Streifen der Reihe nach in die vertikalen. Dabei murmele ich: Drunter, drüber, drunter, drüber, um mich nicht zu vertun – denn obwohl diese Handarbeit simpel ist, passiert es durchaus, dass ich falsch webe und zwei, statt nur einem Streifen, überdecke. Ist der horizontale Streifen eingewebt, drücke ich diesen vorsichtig an die vorherige horizontale Reihe. Dennoch entsteht ein Versatz ca. 5 mm je Streifen in die untere Richtung, so dass am Ende von der zweiten Fotografie ein breiter Streifen übrig bleibt. Je weiter ich webe, desto mehr entfernen sich die horizontalen Bildstreifen von ihrem vertikalen Double.

Als würde man auf ein Bild mit riesigen Pixeln schauen, bei dem der Ausschnitt derart vergrößert ist, dass der Betrachter nichts mehr erkennt. Oder als wären zwei identische Musikstimmen falsch synchronisiert, so dass die zweite Stimme immer weiter hinterherhinkt und ein disharmonischer, aggressiver stakkatoartiger Rhythmus entsteht.

Immer wieder bin ich überrascht, wie ein solches ineinander gewebtes Duo am Ende aussieht – ich kann die entstehende Wirkung nicht vorhersehen. Die Papierstreifen in der Hand zu halten, zentriert meinen Blick auf die Details, die ich sozusagen herausschäle. So sehe ich sich im unregelmäßigen Rhythmus wiederholende Klimaanlagen oder eine Reihe baugleicher Balkone, variierend nur durch die unterschiedliche Nutzung, mal als Wäschedepot fungierend oder ungenutzt und leer. Die analoge Technik des Fragmentierens empfinde ich dabei als viel intensiver als hätte ich diesen Schritt mittels Bildbearbeitung am Computer vollzogen.

Für mich mündet das in Streifen Schneiden und erneut Zusammensetzen des Gesamtbildes in eine genauere Wahrnehmung der Gebäudearchitektur. Interessanterweise wende ich mich dem Bild zu, während ich es zerstöre. Aus Sicht fotografischen Handwerks investiert man normalerweise für ein Foto eine Hundertstel Sekunde, die Zeit, die zur Aufnahme benötigt wird. Anders ist es beim Zerschneiden und Weben. Hier fällt mir, während ich mit dem Messer die Balkone eines 44. Stocks vom Rest der Struktur trenne, auf, dass zwei benachbarte Wohnungen die gleiche Kinderwäsche über die Wäscheleine gehängt haben. Sind die Familien befreundet? Hier wohnen Menschen. Sie haben schillernde Leben, von denen ich als Fotografin nichts weiß. Als Foto-Weberin erfahre ich mehr über sie. Ich lasse mich, auf das was ich zerschneide und wieder verwebe, ein.

Architektur und Stadtplanung sind, auch heute noch, fast ausschließlich in männlicher Hand. Dieser “Selbstverständlichkeit”, stelle ich eine ursprünglich traditionelle weibliche Technik entgegen: das Weben. Was zunächst harmlos erscheint, entpuppt sich als subversive Geste: Ich zerstöre Architektur und verwebe sie aufs neue. Linien und Formen fallen auseinander, die Bildebene bricht auf und erlaubt – so scheint es mindestens – den Blick auf etwas “dahinter”. Wo die Balkone ins Tanzen geraten, kommt wieder etwas Freude, Spiel und Luft in die stringente Ordnung.

Woven Staccato

Enthusiastically cutting up one‘s own photographs is an aggressive act. I run the cutter along the plunging lines of an aging high-rise in Hong Kong, Kowloon, cutting the A1-format (23 3/8 x 33 1/8 inches) photograph into vertical lines (all but the top half-inch, so the strips don’t fall apart). Then I take a second print of the same picture and follow the horizontal lines along the window and balcony parapets with the cutter. It’s as if I’m lovingly tracing the architecture of the house with its projections, air conditioners, window grilles. I hold loose narrow strips in my hand, which I then number on the back.

Now I apply an old cultural technique and weave the horizontal strips one after the other into the vertical ones. While doing so, I mumble, “Under, over, under, over,“ so as not to make a mistake. Although this handiwork is simple, it may happen that I weave incorrectly and cover two, instead of just one strip. Once the horizontal strip is woven in, I carefully press it up against the previous horizontal row. Nevertheless, there is an offset of about 5 mm per strip in the lower direction, so that a wide strip remains at the bottom of the second photograph. The further I weave, the more the horizontal picture strips move away from their vertical double.

It’s like looking at a picture with gigantic pixels that is enlarged to such an extent that the viewer can no longer recognize anything. Or as if two identical musical voices were synchronized incorrectly, so that the second voice lags further and further behind, creating a discordant, aggressive staccato rhythm.

I am repeatedly surprised how such an interwoven duo looks in the end – I can’t predict the resulting effect. Holding the paper strips in my hand focusses my gaze on the details which I sort of extract. Thus I see air conditioners repeating in an irregular rhythm, or a series of identical balconies, varying only by their different uses, sometimes for drying laundry, sometimes unused and empty. I find the analog technique of fragmenting much more intense than had I done this by using an image processing program on the computer.

For me, cutting into strips and reassembling the entire image results in a more accurate perception of the building’s architecture. Interestingly, I dedicate myself to the image when I destroy it. Generally in the art of photography, the photographer invests a hundredth of a second in a photograph, the time it takes to snap the picture. Cutting and weaving is different. Here, as I use a blade to separate the balconies of a 44th floor from the rest of the structure, I notice that two neighboring apartments have the same children’s laundry hanging over the clothesline. Are the families friends? People live here. They have enigmatic lives that I, as a photographer, know nothing about. As a photo weaver, I learn more about them. I become involved with that which I dissect and weave together again.

Architecture and urban planning are, even today, almost exclusively in the hands of men. I contrast this „standard“ with a handicraft traditionally performed by women: weaving. What at first seems harmless, turns out to be a subversive gesture; I destroy architecture and re-weave it. Lines and forms disintegrate, the image is dissolve and allows – or so it seems – a glimpse of something „behind“ it. Where the balconies start to dance, some joy, play and air return to the stringent order.